First as Farce, Then as Tragedy:

Chronicling Transactional Storytelling from Drakengard to NieR: Automata

“No one stops!”

– Popola, NieR (2010)

“This cannot continue.”

– Desert Machines, NieR Automata (2017)

Nier: Automata recently released to nearly universal praise. In this essay, I intend to examine the game’s overarching themes and evaluate the mechanisms of storytelling contributing to its unique accomplishments.

I. A Boring Treatise on The Paradox of Games as Art

Six years ago, I made a video mocking the idea of video games qualifying as art. The core conceit basically focused on the void of a literary canon in popular games, evidencing its deficiency as a medium. The video was mostly comedic in intention, poking fun at self-conscious gamers who felt compelled to validate their hobby as high art, as if they weren’t entitled to enjoy it otherwise. My satirical defense of artistry within the medium picked out games like Dead Space, Red Dead Redemption, and Gears of War – such low-hanging fruits that I almost threw out my back making fun of them.

My thoughts on the subject have matured since then, but I maintain that video games suffer inherent structural limitations that hinder their chances of artistic achievement. The first limitation comes from the division of labor.

Traditionally, high art is often thought of as a harmony of the elements, where every component of a piece interacts with every other component to generate a larger meaning that is (hopefully) greater than the sum of its parts. This is more feasible in mediums such as books or paintings, since a single creative agent often oversees every aspect of a piece’s construction. What is ultimately rendered is a gestalt of an individual artist’s (or a small group’s) conscious efforts. When an artist fails to make a piece interact positively with its own composition, it leads to bad art – and the more complex the undertaking (such as a film or a game), the more craftsmen you need to carry it out. This raises the probability of incongruity and sloppiness – not just because of the workforce’s size, but also the diversity of the roles the craftsmen play. Feature films are frequently made by hundreds of people, all working very specialized tasks: writing, lighting, editing, visual effects, acting, costuming, sound mixing. The role of the director is to ensure that these varied undertakings all contribute to a unified, greater whole. Particularly strong directors who micromanage every element of a film eventually produce something of a signature style. This is the foundation of auteur theory. Auteurs are few and far between, and not even necessarily good; you could consider Neil Breen or Tommy Wiseau as deserving of the title as Wes Anderson or Quentin Tarantino. But the point remains that strong directorial vision has a much greater likelihood of producing art than some ghost in the machine from the disjointed efforts of hundreds of employees.

In the case of video games, this gets even more complicated, as the disciplines of craftsmen are further scattered. Digital artists, computer programmers, level designers, and QA testers team up with writers, voice actors, and composers whose respective fields are often difficult to synergize. It’s difficult, though not impossible, to reconcile the aesthetic with the technical. But even games that are praised for their writing and storytelling often do so entirely through the strength of their writers, rather than taking advantage of the medium. Most games with acclaimed stories, many of which I enjoy, do employ the language of cinema, instead of exploring the potential of games. The Last of Us, Mass Effect, Metal Gear Solid, all of them play out as two separate works: the game and the story. Playing Uncharted and seeing Nathan Drake portrayed in cinematic cutscenes as a suave, charming jokester with compassion for his friends fails to translate into gameplay, where Drake kills people in the hundreds to satisfy his lust for adventure. The term commonly applied here is “ludonarrative dissonance,” and it’s indicative of gaming’s wasted potential to actually create significant art while recycling the techniques of cinema ad nauseum.

The other great hindrance to games as art comes from the conflicting goals between those two idenities. A “game,” by design, is supposed to be fun. At least, that’s what the critical circuit ostensibly cares about. Games are evaluated on their level design, their combat, their graphics. If a game gets all of this right and has a bad story, it’s still an 8/10. If a game has a great story but is frustrating to play, it’s a 3/10. The top priority, among the majority of critics and gamers alike, is gameplay, and by definition, gameplay should be fun. To be boring, frustrating, or otherwise un-fun is the worst sin a game can commit. If it has a decent story, that’s merely a consolation prize.

This inherently limits the material a game can cover. Can a game tastefully cover profane and taboo topics while still being “fun”? There should be merit in something that covers a repulsive topic and, if crafted skillfully, is also repulsive to play. Such executions of this kind of material have a rich history in cinema, literature, music, and the visual arts. But it’s rare to games. This is less of a condemnation than a diagnosis – one that is, thankfully, not universal.

Yoko Taro is a Japanese video game director and writer working for Square Enix. He has seemingly made it his life’s goal to prove wrong all of my initial dismissals of the artistic potential in games. Notoriously reclusive, ambiguously antisocial, and undoubtedly provocative, his work on the Drakengard and NieR series have proven that the aforementioned limitations can be overcome in previously unsuspected ways.

The key component behind his success as an artist is his willingness to transcend the lukewarm imitation of film and offer unrivaled and irreproducible interaction between the way his stories are read and reacted to by players, facilitating a transactional process that integrates them as storytellers.

This piece will focus primarily on an interpretation and analysis of Yoko Taro’s recent masterpiece, NieR: Automata. However, I would like to take a brief look at the previous entries in his series to provide context for his overarching thesis – namely, its preoccupation with killing.

II. A History of Violence

*This section contains spoilers for Drakengard and NieR*

Yoko Taro’s directorial debut, Drakengard (Drag-On Dragoon in Japan), was released in 2003 to middling praise and universal confusion. The story follows Caim, a soldier in a medieval land fighting against an evil empire backed by a sinister cult. Other characters round out the cast, including a pedophilic hermit, a cannibal woman with a taste for children, and a five-year old high priestess who speaks with the baritone voice of an older man. The game boasts multiple endings that grow increasingly disturbing as they go along. The first ending features a positive, if somewhat bittersweet resolution to the story. However, by the time the player reaches the final path, the whole world has gone to hell. Giant cannibal babies descend from space and devour most of the characters. In a final desperate act, Caim and his dragon, Angelus, attack the queen of the monsters, which transports them to modern-day Shinjuku, Tokyo. They then proceed to have a rhythm battle over the Tokyo skyline, where Caim defeats the queen, causing it to disintegrate and cover the city with salt. Then Caim and Angelus get intercepted and killed by the Japanese air force. Then it’s over.

The insanity of Drakengard’s plot speaks for itself and hardly went unnoticed in its time, but the way in which it interacts with the other elements of the game elevates Drakengard’s narrative from a nightmarish hallucination to an experimental piece of digital literature.

As many reviewers quickly pointed out, Drakengard is not fun. The combat is monotonous, the mission objectives are often vague and frustrating, the user interface is unintuitive, and the overall atmosphere feels bleak and oppressive – not something you’d typically find in one of Square’s RPGs. The disturbing atmosphere of Drakengard is an essential component of its narrative. The game’s infamous soundtrack was arranged by sampling and shuffling pieces of classical symphonies together to produce a cacophonous mess that assaulted players’ eardrums during every moment of gameplay. The dissonance of these tracks grows more extreme as reality crumbles in the main scenario, leading to bizarre mid-note halts and other disorienting effects. Nonetheless, the uncomfortable soundtrack provides the perfect backdrop for an uncomfortable story about child soldiers, mass murder, incest, and a host of other disturbing things. It always seems like Drakengard has it out for the player, culminating in its unnerving and borderline unbeatable final boss.

Games have explored taboo subjects like these before, but only Drakengard consolidated a formal and thematic union between gameplay and story. As the game progresses, players soon realize that the protagonist, Caim, is a severely disturbed individual who revels in wanton murder. Mercy and compassion, as concepts, fail to register with him. Every level is effectively another leg of Caim’s endless rampage. But the game doesn’t just tell the player to be repulsed by their actions via cutscene. Rather, the player’s disgust is naturally incubated through the grueling experience of traversing battlefield after battlefield and killing everything that moves. In a medium where violence is the standard, where characters kill by the dozens or hundreds and stay “heroes”, where violence is either kept at a distance, sanitized, or even celebrated (“Congratulations! You defeated 100 enemies!”), Drakengard uses every textual force at its disposal to make itself unpalatable to players. Drakengard is the video game equivalent of the Ludovico technique from A Clockwork Orange. The narrative cannot be ignored, because it’s woven into every component of the game. Drakengard conveys its message by making you hate it.

The psychosis of the characters, the chaos of the world, and the dissonance of the music all build the game’s central thesis: the insanity of violence. What type of person do you need to be in order to kill like a video game character? What type of player do you have to be to prolong the cycle of violence via multiple playthroughs, only to receive grimmer and grimmer endings? Drakengard made an unparalleled achievement for its time: it resolved ludonarrative dissonance.

Drakengard received a sequel (Drakengard 2) and a prequel (Drakengard 3). The second game barely warrants mentioning. Yoko Taro’s involvement was severely limited, and Square handed off the writing and directing duties in the hopes of making a less-gruesome, more-marketable game. Despite Drakengard 2 making noticeable improvements to combat mechanics (i.e. making them more fun), it lacked much of the appeal of the first game and has since fallen to the wayside with fans. The game is even quarantined to its own pocket timeline within the franchise’s larger continuity, effectively removing it from most plot or lore-related discussions.

Drakengard 3 saw the return of Yoko Taro and his signature dark atmosphere, although it seems more concerned with world building and self-parody than breaking narrative ground like the first game did. It has plenty of amusing moments, but it ultimately doesn’t say much and feels more like wiki-fodder than anything. Still, it’s a refreshing take on the series and proof of Yoko Taro’s range as a writer.

But a few years prior to Drakengard 3, Yoko Taro wrote and directed an alternate sequel to Drakengard, taking place after the game’s fifth and final ending – the one with the Tokyo battle. This new title, NieR, advanced the line of inquiry started in Drakengard and expanded it tenfold.

NieR was released in 2010 to mild praise, but has since developed an immense cult following. The game takes place in a post-apocalyptic future where small pockets of humanity try to carry on normal lives amidst the threat of entities known as Shades. In contrast to the oppressive atmosphere of Drakengard, NieR’s elegiac tone is underscored by Keiichi Okabe’s beautifully somber score, which went on to inspire several arrangements and tribute albums.

Critics heaped praises on NieR for its writing, voice work, and delightful characters. At first glance, its more subdued, elegant content may seem less challenging than the audacious Drakengard, but NieR’s brilliance lies in how it approaches the same questions posed by its predecessor from different angles. And ultimately, it comes to a different conclusion.

As the player controls the eponymous lead character on a quest to save his ailing daughter, the game comments on the cycle of violence that mankind unknowingly perpetuates. This is achieved through appealing to Nier’s (and by extension, the player’s) sense of heroism. Unlike Caim, Nier possess a kind heart and genuinely wants to make the world a better place, even though his daughter’s wellbeing always comes first. The first half of NieR sees the protagonist embarking on a decidedly video-game-style adventure. He takes on mini-quests to help out villagers, mocks boss designs ripped straight from Zelda, engages in a bizarre text-adventure sequence, and explores a mansion that’s blatantly reminiscent of the original Resident Evil. The first half, while not entirely devoid of drama or pathos, affectionately parodies popular games and the conventional baggage they bring with them. Grimly, this includes our lovable cast’s penchant for solving problems with their weapons.

The second part of NieR descends into full-blown tragedy. Violence between the humans and Shades increases dramatically, and several characters are driven mad with grief. By the conclusion, Nier and his friends discover that humanity as we know it has long since died out. Using power extracted from the corpse of Caim’s dragon, humans devised a way to survive the apocalypse by separating their souls from their bodies. A collection of soulless clones known as “Replicants” were to tend to the world as it recovered over the course of centuries, before the souls (known as “Gestalts”) returned to their corresponding bodies. Unfortunately, the Replicants, including Nier and every other supposed human in the game, developed a sense of consciousness and fought back against the Gestalts, leaving them to wander the wilderness as the feral Shade creatures. Nier himself is the clone of the Shadowlord, a Gestalt presiding over the entire system. The Shadowlord labors to recover the corresponding bodies for himself and his daughter, with the eventual goal of restoring humanity. In the end, Nier remains loyal to his convictions, puts the safety of his daughter over all else, and slays the Shadowlord, which precipitates the collapse of Project Gestalt and effectively dooms all Replicants and Shades to extinction.

Yoko Taro once again uses multiple playthroughs as a means to enhance the story. Subsequent laps through the game have the Shades’ dialogue translated, revealing them to be just as emotional and human as the Replicants. In fact, many of their fatal encounters with Nier turn out to be misunderstandings driven out of control by Nier’s prejudice and myopic obsession with saving his daughter. Nier and his friends remain sympathetic characters throughout all of this, but the player now sees instances of supposed heroism, altruism, and duty in a different light. The conflict between the Gestalts and Replicants is irreconcilable and unavoidable, but neither side is right or wrong. Yoko Taro admitted that NieR’s story was inspired by the September 11th attacks and the resulting War of Terror. He expressed dissatisfaction with the conclusion he came to in Drakengard – that you have to be crazy and cruel to commit mass murder – and sought to tell a story about two equally sympathetic sides willing to annihilate one another out of necessity, idealism, or justice. The fact that Nier’s actions lead to humanity’s demise laments the inevitable suffering brought by such conflict.

Whereas Drakengard obsesses over the insanity of violence, NieR ponders the banality of violence. Again, the player is implicated in this. They undertake quests to help distressed villagers, willfully ambivalent towards the Shades they kill to do so. Video games have often been described as power fantasies, and I posit that the opportunity to be a larger-than-life hero contributes to this phenomenon. Nier is certainly devoted to his daughter’s well-being, but rather than stay at home and comfort her as she suffers from a terminal illness, he jumps at the opportunity to embark on a wacky adventure to find a cure, accompanied by his magical talking book. Nier is easily manipulated into his journey by a bogus prophecy contrived by Devola and Popola, his long-time friends and hidden agents of the Shadowlord. Throughout the game, loading screens convey letters from Nier’s sickly daughter, praying for him to come home and spend time with her. After the Shadowlord’s defeat, her illness isn’t even cured. The only thing Nier wins from his adventure is the downfall of humanity. Nier’s heroism contains a component of egotism, as does any player’s. The consequences of your actions retroactively pervert the good-natured fun and humor of the earlier sequences. What began as a light-hearted Grail Quest escalates into a series of massacres where nobody can possibly “win”. Through repeated playthroughs, Yoko Taro takes Karl Marx’s famous aphorism, “First as tragedy, then as farce,” and inverts it. He leaves the player’s previous sense of heroism invalidated.

Nier receives one last chance at redemption, though. A chance to be a true hero, uncorrupted by subliminal selfishness. When his friend, Kainé, lies on the brink of death, Nier has the choice to sacrifice his life in place of hers. But there’s a catch: nobody will ever remember he existed. This final scene puts Nier’s altruism to the ultimate test, providing him the opportunity to do something inherently selfless. The player, meanwhile, also has to face consequences. A lesser game would simply have you pick between saving Nier or Kainé, effectively making any element of sacrifice arbitrary; after all, the player wouldn’t be giving anything up. But NieR’s legendary ending issues the player an ultimatum to prove their commitment: erasing Nier from existence leads to the deletion of all of the player’s save data. In order to see the ending, the player needs to sacrifice everything they’ve worked so hard to obtain. It wipes away all records of their accomplishments. This unique storytelling technique imbricates the personal experience of its audience with the central message of the narrative.

And yes, it actually does delete all of your save data.

The tragedy of NieR’s story complements the tragedy of its production. Cavia, Inc., Yoko Taro’s company, folded shortly after its release. The creative team poured everything into the game, but its sales were nonetheless dismal. NieR released between Mass Effect 2 and Final Fantasy XIII. No low-budget JRPG could compete with those giants.

Year later, NieR received a surge in popularity. Yoko Taro teamed up with Platinum Games to produce a sequel with a significantly higher budget: NieR: Automata.

III. I Actually Start Talking About NieR: Automata Here

After fourteen years of critical and commercial disappointment, the cultural zeitgeist finally caught up with Yoko Taro. Automata is nothing short of a masterpiece. By collaborating with Platinum, Yoko Taro succeeded in delivering a smooth gameplay experience that satisfied players’ demand for fast-paced, visceral combat and boss design. Combined with compelling characters, breathtaking visual direction, and one of the most beautiful scores in recent memory, it seemed like he had finally created something that could have mass public appeal. But does Automata live up to the lofty standards of digital storytelling set by the previous titles?

Any explanation offered here, regardless of its length or thoroughness, would inevitably fail to capture just how effectively Automata is designed. For this reason, I intend to limit my discussion to an analysis of the major motifs and themes present in the narrative, and investigate how they capitalize on their medium for added poignancy.

IV. Sex, Violence, and the Evolution of the Drakengard Discourse

*This section contains spoilers for NieR: Automata*

Automata takes place thousands of the years after the original NieR, telling the story of androids 2B, 9S, and A2 as they battle foreign machine lifeforms in a proxy war between humanity and alien invaders. Under the command of YoRHa, an android military program, they fight on behalf of human refugees sheltered on the moon, all the while contemplating the futility of the seemingly endless war. Despite their combat-oriented programming, both androids and machines nonetheless possess the capacity for emotion, including sympathy, love, and sexual desire.

Early in the game, 2B and 9S stumble upon a community of desert-dwelling machines who imitate sexual acts despite not possessing genitals. The two soldiers walk in on an immense robot orgy, complete with uncoordinated machines thrusting their featureless groins together and attempting to perform cunnilingus without proper mouths. The whole spectacle is as cute as it is disturbing. The player is reminded of children playing “house”, imitating adult life while only understanding it on a superficial level. Yet miraculously, the machines’ fruitless gyrations end up birthing a single, humanoid offspring, fully-grown. This scene introduces Adam – a major antagonist, brought into being moments after a chorus of amorous declarations and relentless copulation, only to immediately be introduced to violence when 2B and 9S attempt to kill him. Though Adam survives the initial encounter, the violence inflicted upon him influences his subsequent worldview and perception of desire.

Adam, along with his twin brother, Eve, was sculpted by the machines in the image of the elusive humans, whom the machines revere over their alien progenitors. In fact, an early revelation shows that the machines already wiped out the aliens, whom Adam describes as “simple” and “plant-like”. Adam harbors a fascination for humans, specifically because they “loved and killed in equal measure.” Adam, who emerged from his metal womb devoid of genitals and experienced his first moment of intimacy at the edge of a sword, views sex and violence as two sides of the same coin, inextricable from the human experience he so desperately seeks to emulate.

Other machines share Adam’s presumptions. Simone [Beauvoir], a hostile opera singer, cannibalizes androids and machines alike in the hopes of obtaining beauty and desirability. A ragtag theatre troupe performs their own twisted rendition of Romeo and Juliet, which quickly descends into a spectacle of mass murder as the two titular lovers massacre one another (and their doppelgangers; more on that later).

The YoRHa androids, likewise, aren’t exempt from the association of sex and violence. 2B and the other combat units all sport racy outfits with frilly skirts and high heels. Like the machines, they exaggerate the aesthetic to the point of absurdity. But a side-quest with the character Jackass reveals an interesting aspect of the androids’ synthetic brain chemistry:

“See this reaction? It proves that android brains contain an algorithm which allows them to derive pleasure from battle! Without that, we’d probably have stopped fighting a long time ago. What a brutally efficient piece of evolution!”

Jackass’s discovery not only explains the borderline Pavlovian association of sex with violence instilled in all androids, but also contextualizes a key part of the gameplay experience: the combat system, as experienced by the player. Subjective as such an assessment may be, Platinum Games is renowned for their refined combat systems, which typically prioritize intense, visceral battles that are both visually and mechanically stimulating. When Automata was announced, many fans were overjoyed to hear about Yoko Taro’s collaboration with Platinum, since they typically viewed the fighting mechanics as a major weak point in his previous titles. Indeed, much of the positive reception Automata garnered from critics came from the improved gameplay. It made all the difference, allowing the game to earn commercial and critical success beyond expectations. But Automata in no way sacrifices narrative cohesion for the sake of more fluid, entertaining combat. Rather, it uses the orgasmic feelings generated from bombastic enemy encounters and ferocious boss battles to clue the player in on the psychology of the androids. As Jackass states, android would’ve been driven to despair or insanity by the eternal war with the machines had it not been for their rhapsodic indulgence in the thrill of battle. Whereas Drakengard sought to make violence unsavory, Automata strives to make it fun, but it nonetheless shares its predecessor’s disturbing implications. In the world of Automata, violence acts as a bulwark against madness.

Drakengard expressed the insanity of violence. NieR expressed the banality of violence. NieR: Automata expresses the necessity of violence. And with each passing game, the gameplay becomes more fun, though not to the detriment of its thematic substance.

So what happens when violence isn’t fun? 9S possesses obvious romantic feelings for 2B, but she remains cold and aloof. As a non-combat model, 9S’s duties lack the excitement or reward that units like 2B and A2 receive. Among the game’s notable criticisms, the most prevalent one comes from a general dissatisfaction with 9S’s gameplay style. Most players find controlling him significantly less fun than the other two, as 9S isn’t designed for the thrilling close-quarters combat enjoyed by them. Even 9S complains about the tedium of his hacking job at certain points. Considering what we’ve learned about android brain chemistry, it’s easy to understand how 9S can be sexually frustrated – and how that frustration contributes to the madness that consumes him in the third act.

After 2B’s death, 9S launches a rage-fueled vendetta against the machines and A2. As he grieves over her, his behavior grows increasingly erratic and violent. The true perversity of this rampage isn’t revealed until just before the end of the third playthrough. It turns out that 2B was, in actuality, a specialized Executioner unit designed to murder 9S when he inevitably discovered the truth about humanity’s extinction. In fact, 2B had already killed 9S several times in the past – he just lacks total recollection of his previous incarnations, or willfully denies it. 2B’s cold demeanor towards 9S, her constant insistence that “emotions are prohibited” whenever he tried to get close to her (despite the fact that none of the other androids, 2B included, abide by this rule in any other context), all serve to shield her from the pain of her murderous duty.

Nonetheless, 2B retains feelings for him. When Eve infects 9S with a logic-virus at the end of the first playthrough, he begs her to kill him. She tearfully obliges, straddling his prone body, wrapping her hands around his neck, and thrusting her hips against him suggestively as she chokes the life out of him. A perceptive player will notice the perversity of the scene even prior to the endgame revelation. After she’s finished, she laments that it “always ends like this,” alluding to her true assignment well before it’s brought to light.

A part of 9S, however, seems to recognize 2B for what she is, despite being unwilling to accept it. When 9S slays a machine construct manipulating his memories within his mind’s digital world, it turns into 2B upon its defeat. This scene inverts the previous one, with 9S mounting 2B’s corpse and repeatedly thrusting his sword into her chest, spewing blood with each plunge. His sexual fantasies intertwine with his violent instincts, and together they act as a therapeutic outlet for his grief – if a bit too little, too late.

In one of the game’s most controversial scenes, Adam captures 9S and, via a text-only interface, expounds on his obsession with conflict and hatred. Immediately following his diagnosis of 9S as someone who wants to both “destroy everything” and “be loved by all,” Adam drops this bombshell:

“You’re thinking about how much you want to **** 2B, aren’t you?”

At face value, most players assume that the censored word is “fuck”. But other instances of “fuck” go completely uncensored – it’s an M-rated (17+) game, after all. However, after finishing the story, many have posited that the four letter word is, in fact, “kill”, an idea infinitely more profane and more likely to be rejected by 9S’s mind. The Japanese text is likewise obscured. The ambiguity of the statement, especially considering Adam’s preface, enhances the overlap between ideas of sex and violence among Automata’s cast. 9S wants to love 2B, physically and emotionally, but still struggles to repress the lifetimes of anguish she’s caused him. The irreconcilable nature of the conflict pushes his grief to insanity.

The final symbol of this paradox comes in the shape of the game’s penultimate boss – Ko-Shi/Ro-Shi. This boss is a fusion of two separate entities: a black sphere, Ko-Shi, whose name is derived from Kong Fuzi – and a white sphere, Ro-Shi, whose name is derived from Laozi. Both philosophers are associated with Taoism, and the duality of their combined form represents the symbol of the yin and yang. Moreover, the black and white color scheme already appeared on the signature weapons and vehicles of 9S and 2B, respectively. The union of these two souls, of these two ideas, literalizes in the form of a mechanical abomination, a contradiction 9S has to face and overcome.

The mixture of pleasure and pain, a fun action game with a bitterly critical story, conveys itself in such a manner that it could not be represented in any other medium. NieR: Automata follows in the footsteps of the previous games by speculating on the nature of violence and how an audience interacts with it in game form. Yoko Taro crafted the characters’ personal journeys to complement the emergent narrative contributed by the player. Automata’s conclusion to the question of violence differs from Yoko Taro’s previous outings without losing any of its profundity.

V. What’s in a Name?

*This section contains spoilers for NieR: Automata*

One of Yoko Taro’s greatest assets is his ability to turn seemingly innocuous bits of humor or fourth-wall breaking into serious dramatic content. He drafts every silly one-off joke or character quirk into the service of a larger idea within the narrative. Foreshadowing in stories often tends to match the tones between the setup and payoff – if the setup is funny, it will typically appear later for a comedic bit, whereas a more grave scene portends something of similar significance. Yoko Taro games, on the other hand, often contain jokes, camp, or awkward genre-blending, as seen with the text adventures and general video game satire in the first half of NieR, that reemerge with vastly different implications further in the story.

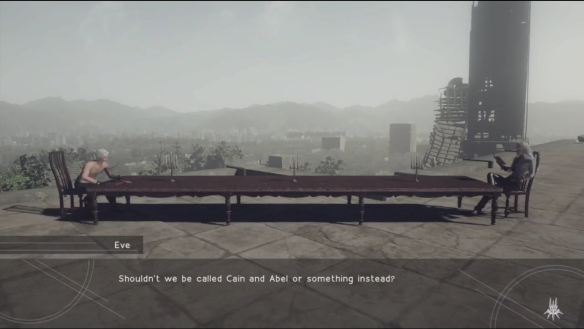

Adam and Eve’s names derive from the Biblical origin story of Genesis. However, both of the siblings in Automata are male, as Eve points out in one of his conversations with his brother. Eve, studying the Bible at Adam’s behest, suggests that it would make more sense to call themselves Cain and Abel. Adam dismisses this suggestion, citing that humans (the mythical beings in whose image they were created) rarely changed their names. An initial reading of the scene gives the impression of a warm, if somewhat dysfunctional relationship between the two, and the whole dinner table conversation screams of a domestic sitcom. Another layer of humor can be found in Eve’s criticism of the misappropriation of Christian imagery, a prevalent issue in JRPGs like Xenogears, Final Fantasy, and Shin Megami Tensai. Yoko Taro capitalizes on the machines’ collective naiveté to poke fun at industry trends that frustrate him. From 2B’s opening monologue, he prompts player expectations about killing God, an exhausted trope in JRPGs, only to tragically turn this supposition on its head later on. If God is described as a creator and one who defines the purpose of existence, then humans are the undisputed gods of the androids. The humans, however, are extinct. 2B can never get the chance to kill God, because God’s already dead. This sinisterly humorous inversion makes fools out of the androids and genre-savvy players alike, but it also denies the androids the opportunity to rebel against their fate. If God was a ship’s captain, sailing along his planned course against the will of his crew, mutiny could change their fate. But with no God, no plan, no ship, no wind, the androids lie adrift in an empty sea – a fate more frightening than a cruel captain.

Moreover, the joke about Adam’s namesake underlines his ignorance of its original meaning, embracing it on superficial levels only – a quality he shares with many of his machine brethren. He instructs Eve to eat an apple, despite having no need for sustenance in such a form, hoping that it will bring them knowledge. But traditional Biblical interpretations view Adam and Eve’s eating of the Fruit of Knowledge of Good and Evil as a negative thing that stole their innocence and lost them the grace of God. Adam likewise insists on the two of them wearing clothing in order to be more human, which their counterparts only did out of shame. In fact, neither Adam nor Eve possess visible sexual organs when nude, further drawing the function of the imitation into question. They may not possess a sense of shame; or rather, they may be celebrating shame as part of the human condition.

When 9S delves into machine records, he notices that machine societies often try to set up governments, but never learn from their mistakes. Despite showing remarkable adaptability in combat, a machine city will continuously overthrow despots and install new ones on the spot, despite knowing the disastrous consequences. At first, 9S expresses frustration at the machines’ stupidity, but then he considers an alternative explanation: the objective is failure. To legitimize their cargo cult, the machines, along with Adam, identify the most efficient ways to mimic humanity’s failings. Adam’s final moments come when he disconnects himself from the machine network, which granted him effective immortality, in order to fight 2B with a proper fear of death that inspired so many human emotions. Mortality represents the final enigma in his obsession with humans, and just as the Biblical Adam was condemned to death by his lust for knowledge, so too is the Adam of Automata.

Another powerful example of farce turned tragedy is a humorous stage play performed by machines: “Romeos and Juliets”. In the play, which occurs in the middle of a bizarre side-quest as a one-off gag, three Romeos and three Juliets fail to identify one another and attempt to resolve the issue through a process of elimination – literally. It seems the only part of the play that resonated with the machines, despite their childlike innocence and earnest desire to entertain, is its notably gruesome ending, and an exaggerated rendition, at that. An audience member, identifying it as old world literature, suggests that it speaks to humanity’s capacity for cruelty. Even this interpretation is meant to provoke a laugh from the player, as so many of theatre goers find themselves deeply moved by the infantile display (save for one cynic; you can’t please everyone). Fans typically regard “Romeos and Juliets” as one of the game’s funniest moments.

Nevertheless, the play also foreshadows the climax of the story. When climbing the machines’ tower, 9S encounters hostile copies of 2B. Approaching hysteria, he promises to kill them all because they’re not his 2B. The parallels further crystallize after 2B’s purpose as an Executioner is revealed. She, likewise, has slaughtered 9S countless times. What was once humorous when performed on stage mutates into a tragedy of destructive catharsis. 2B and 9S, eternally star-crossed, take turns killing each other until a single, suicidal survivor emerges.

“Romeos and Juliets” functions within A2’s story as well. While she climbs the tower concurrent with 9S, she encounters the Terminals – the cores of the machine network responsible for wiping out her squad years ago, who constantly strive to evolve in a human-like direction. During her battle, A2 and her Pod discover that the Terminals keep replicating every time she kills one, and that they’re evolving too quickly for her to defeat them all. So rather than fight back, she adopts a new strategy: she lets them evolve, lets them replicate, until the Terminals start fighting amongst themselves. Some consider A2 a threat to be neutralized; others recommend keeping her alive, as her continued resistance would provide an opportunity to evolve further. The humanoid intelligences become divided by their ideologies and, in an accelerated, microcosmic simulation of human history, they wipe each other out. This clever resolution, though achieved via nonviolence (definitely reflective of Yoko Taro’s stance on war), actually does speak to humanity’s capacity for cruelty, and harbors a pessimistic prediction on the end result.

As noted, humor and drama make for strange bedfellows in Yoko Taro’s work. If we recall the original Romeo and Juliet, Juliet muses “What’s in a name?” In NieR: Automata, quite a bit. The story overflows with references to existential philosophy, both subtle and painfully obvious.

It feels silly to even write this, but 2B’s name is a pun on “to be”. The game makes this all but explicit. 9S, similarly, may derive his name from the German “nein ist”. The grammar isn’t quite right, but such a statement could be interpreted as “is not”, and Yoko Taro has a history with naming characters with both German words and numbers. A2 likely represents the French and Latin “Et tu”, meaning “and you”. This probably refers to her outlier status among the YoRHa units, along with the fact that she only joins the cast midway through the game.

Most of the bosses take their names from famous philosophers, and many of them meet their ends in ironic ways. Ko-Shi and Ro-shi I’ve already discussed. Marx and Engels reside in a factory that their real-life counterparts would’ve abhorred, and they’re killed once 2B seizes their means of production. Simone [Beauvoir] obsesses over beauty and femininity until they lead to her demise. Kierkegaard passes away and “becomes a god” in his bizarre death cult. Immanuel [Kant] inhabits the body of infant machine, acting as an amazing double-pun on the Christ child and Kant’s own beliefs on the agency of children. Also, Yoko Taro may or may not be comparing Kant to a literal baby. Other examples, such as Pascal, Hegel, Auguste [Comte], Jean-Paul [Sartre], and Friedrich [Nietzsche] are sprinkled throughout the narrative.

These references, however, go beyond cute parallels and smug lampooning (though that’s definitely present). NieR: Automata dives headfirst into the cloudy waters of existentialist inquiry and invites the player to explore alongside it through its unique gameplay-narrative transactions.

VI. Meaningless Code and Childhood’s End

*This section contains spoilers for NieR: Automata*

The pursuit of philosophy embodies an attempt to find answers for abstract problems. The nature of these problems stems from an imperfection or dissatisfaction with life. In other words, philosophy represents mankind’s attempt to derive meaning from pain. In The Myth of Sisyphus, Albert Camus, who is mysteriously unrepresented among Automata’s cast, explores the logic of suicide as a response to a life that is often painful and, ultimately, transitory and meaningless. Rationalizing life thus involves an indulgence in the absurd, an investment in something that is utterly pointless.

The machines that live independent from the network all fixate on a particular value of human life: love for the desert machines, fun for amusement park’s residents, religion for the factory machines, hatred for Adam, etc. A particular picture book section makes clear that each machine holds a unique “treasure” that grants them purpose:

“Consciousness, pain, joy, misery, fury, shame, desolation, the future… The meaning of life.”

Divergent meanings are also found by YoRHa, the Terminals, Devola and Popola, and 9S – almost all of which manifest as ways of working through trauma. The concept of trauma, wherein an individual either relives a painful experience or carries it with them in the form of depression, posed a unique problem for Sigmund Freud in his book Beyond the Pleasure Principle. If life’s meaning comes from the pursuit of pleasure and happiness, even in the face of willful delusions, then why does the mind, consciously or unconsciously, maintain painful memories beyond practical use? Why would the mind go out of its way to recreate negative stimuli? One theory Freud posits is finding resolution through repetition, either by discovering meaning behind the traumatizing event or fantasizing about a different resolution – both of which prove painful processes that frequently backfire when recalling trauma.

For both the androids and machines of NieR: Automata, physical death is relatively unimportant, but the loss of memory and consequent death of consciousness is. Several times during cutscenes, 2B and 9S trigger their self-destruct protocols in order to escape dire situations and transfer their consciousnesses to separate (but identical) bodies at the android Bunker. The game implements this concept with the player as well; when a player’s character “dies”, they are reincarnated at the nearest save point, but little actual progress is lost. The player loses all accumulated experience points and levels that they earned since their last sync with the android server, but if they find their previous body where they died, they can immediately recover them at no cost.

Androids thus understand death differently: death is the loss of memory, becoming a version of yourself that isn’t you. 9S fails to backup with the Bunker during the first mission, so after his body is destroyed, he needs to meet with 2B for the first time again. 2B’s hellish trauma stems from carrying the memories of meeting and killing 9S over and over again. She’s trapped in a perpetual cycle of life and death, as her opening monologue states, and the burden of her memories shapes her characterization. The pressure this puts on other Executioner-type androids is explored in a side-quest where the protagonists restore the memories of an amnesiac soldier. The soldier reveals her Executioner designation with giddy laughter and explains that she deleted her own identity to escape the trauma.

Android or machine, the erasure of a person’s past is tantamount to suicide. Pascal, a peaceful machine who shepherds a small village, discovers that the children under his care have killed themselves out of fear that he instilled in them for protective reasons. Unable to handle the responsibility or grief, Pascal pleads with A2 to either kill him or delete his memories; since Pascal has no backup or alternate body prepared to house his memory core, the options are effectively the same. A disturbing twist follows if the player deletes Pascal’s memories. Should the player return to Pascal’s vacant village, he will function as a merchant attempting to profit off the “junk” lying around everywhere. He then offers to trade the body parts of the children and other villagers in exchange for money, since they mean nothing to him any longer. The good-natured Pascal’s avoidance of trauma renders him hollow and solitary. Unable to find hope or meaning behind the deaths of his charges, Pascal chooses to end his life, one way or another.

As demonstrated by the cycles of violence in the first NieR, inconsolable grief similarly adopts memetic properties in Automata. After 2B kills Adam, Eve goes on a rampage with no defined goal. When 2B and 9S confront him, he curses them for robbing him of his reason to live.

“I know you two feel the same. That this world… is utterly meaningless. As far as I’m concerned, my brother… was everything… and now… everything must die!”

Eve’s grief-stricken madness spreads to 9S in a quite literal manner. After the fight, 9S gets infected by part of Eve’s consciousness. With the partial fusion of their memory regions, 9S decides that his data cannot be uploaded to the android server, and requests 2B to kill him. Despite his insistence that he can always come back in a new body, 2B laments that he would lose the version of himself that “exists in this moment”, once again foregrounding the interrelation between memory and identity. But even this idea is complicated by the temporary fusion of 9S and Eve’s personalities, along with A2’s incorporation of 2B’s memories later in the game. It seems that identity doesn’t exist in a vacuum, but instead forms through interactions with others, as noted with Pascal. The influence of others exists as a ghost memory in our subconscious, informing the ways we develop, the ways we think and feel, and how we cope with grief. Even after the androids obliterate Eve’s independent consciousness, his footprints guide 9S on a path of nihilistic homicide once he experiences a similar loss. Trauma is sympathetic in nature, hence why players receive the option to side with 9S in the end battle, despite his erroneous logic.

Like the androids and the machines fighting a war on behalf of their masters in absentia, 9S carries out his final violent crusade in the name of 2B. He remains wholly fixated on her after her death, despite the pain it brings. Upon confronting the 2B copies in the tower, he rips the arm off one and grafts it onto himself. He literally can’t let her go, despite his Pod’s warnings of a virus spreading from the arm into his system. He vows to kill the machines and A2 in 2B’s honor, consequences be damned. It’s all he has to live for. When A2 tells him the truth about 2B, he reacts with hostility, even though he’s always suspected it. 9S can’t bear the thought of his fighting being meaningless. The humans he fights for are extinct. The woman he loves has died. The last thing he wants to hear is that she wasn’t worth fighting for. His idealized relationship with her gives him a sense of meaning, and each act of violence on her behalf makes his fantasy feel more legitimate. Delusions and narcotic violence help him cope, but realistically, nothing is solved. In The Pervert’s Guide to Cinema, Slavoj Žižek comments that there’s a name for fantasy realized: “nightmare.”

The larger war functions as a shield for psychological insecurities. Androids risked falling into despair with the death of humanity, so they crafted a grand conspiracy that claimed humanity survived on the surface of the moon. Meanwhile, the machines proved the perfect enemy for the androids to fight and ensure a sense of purpose. The military deadlock guaranteed the truth would never get out, thus allowing androids to retain hope and perpetually contribute to the cause. The Terminals, the nefarious machines that co-opt YoRHa, come across as equally pathetic. Their prime directive is to eliminate the enemy – in this case, the androids, which they could easily do. However, they fear what a future without purpose holds, since their creators are no longer around to designate meaning for them. They decide to extend the war as long as possible, evolving and expanding in consciousness, but always allowing the androids to survive so that the conflict, their reason for existence, persists. Jackass says it best:

“… So then! To sum up: For hundreds of years, we’ve been fighting a network of machines with the ghost of humanity at its core. We’ve been living in a stupid fucking world where we fight an endless war that we COULDN’T POSSIBLY LOSE, all for the sake of some Council of Humanity on the moon that doesn’t even exist.”

The search for meaning behind suffering makes for dramatically heavy stuff, but any work of art exploring a concept like this would need to communicate it delicately, lest the farce-turned-tragedy fall back into farce. After all, the game originally teases this idea with Operator 6O tearfully interrupting the story to whine about being turned down for a date and claiming that she doesn’t know how to “go on living.” So a deft handling of the subject matter is required to keep it from becoming camp. This is where a transactional reading of Automata triumphs.

Players familiar with the first game likely recognize Devola and Popola as mysterious manipulators and late-game antagonists. They reappear in Automata, though it’s not really them. The original Devola and Popola units perished in the final battle of NieR, while the ones in Automata remain among the last of their line of models. Due to the failure of their previous incarnations and the subsequent collapse of Project Gestalt, the new Devola and Popola are ostracized by android society. Their oppressors don’t particularly know what they’re punishing them for, since the predominant belief has humans living safely on the moon. Their prejudice and abuse is more of a cultural custom than anything. But even the twins themselves have internalized their oppression. They believe they exist to suffer in order to atone for the past sins they don’t fully understand. They carry out a degrading existence, rationalizing their pain as deserved retribution. They bear the shame of their predecessors’ faces, despite knowing that they, personally, did nothing to warrant their lot in life.

But Yoko Taro doesn’t merely tell you about this prejudice. Nor does he just show it. He proves it.

Right before 9S enters the tower, the twins appear out of nowhere and brandish their weapons towards him. This almost perfectly mirrors the first game, where they appeared unexpectedly in front of the final level and threatened the heroes. Familiar players, myself included, interpreted this moment in Automata as another sign of their duplicity. A battle seems all but inevitable, but it may only seem that way because of the baggage the characters bring with them – baggage that isn’t their own. The scene promptly reveals itself as a bait-and-switch, with Devola and Popola attacking the machines flanking 9S and offering their lives in his service. They don’t seem to understand 9S’s motivation or the psychotic impetus behind it. Rather, they seek atonement through martyrdom, perhaps the only way they’ll find peace. They die selflessly, hoping they assuaged their false guilt.

The player effectively becomes an actor in this scene, as they’re expected to have an arc. Players ought to assume Devola and Popola’s hostile intentions and liken them to their former versions. But in doing so – and more importantly, being wrong – the game implicates players in the same logic that discriminatory androids use to brutalize the sisters. Contriving a scenario to show prejudice is one thing. Tricking the audience into engaging in it makes its existence undeniable and terrifying. It triggers a sense of revulsion, and further, a pang of guilt – one less burdensome yet more authentic than the one the twins harbor.

By interfacing with the player, Automata employs techniques unfamiliar to other mediums in order to encourage its audience to reflect on the purpose of their playing. For example, the coveted “Achievements” or “Trophies” ubiquitous to modern games, traditionally obtained by completing specific challenging tasks, can be purchased at a shop in Automata. They no longer stand as a testament to skill, but did they ever? Do they have any function beyond the vacuous pursuit of competitive glory? Are they ever an end in themselves? I posit the answers to be “No” across the board. This feature generated controversy upon release, which illustrates both the sanctimonious culture surrounding such trophies as well as the stubbornly resilient desires of consumers to impose meaning on the meaningless, defending it till death.

Even reconstructing the plot of NieR: Automata to fit into the series’ larger cosmology proves a frustrating and unrewarding task. The game teases connections to the previous stories, such as the Red Eye disease, the Cult of Watchers, the demonic flower, and the enigmatic Accord, but a clear pattern never emerges. Meanwhile, fans (myself included), comb over minute details in the vain hope of finding a cohesive explanation. Instead, we draw constellations.

The nebulous lore leaves players as confused as the characters when it comes to the grand plan for the game’s universe. Perhaps no such plan exists. Perhaps Yoko Taro makes it up as he goes along. But perhaps the struggle to find meaning, even in the face of pain, hardship, and potential futility – perhaps that’s the true meaning behind everything.

VII. NieR: Automata’s Groundbreaking Finale

*This section contains spoilers for NieR: Automata*

The [E]nd of YoRHa. Barely a month after release, and this ending has already cemented itself in the annals of game history.

Following the completion of endings C and D, the three protagonist androids all lie dead. As the credits begin to roll, Pod 153 chimes in to report the commencement of a data wipe, her final protocol after the destruction of Project YoRHa. In this sequence, Yoko Taro shows his intimate awareness of his games’ reputation for dark and depressing endings. Pod 153’s plan harkens back to the first NieR, which culminated in a data wipe on the fourth ending. Lines of static stream down with the credits, implying that, once again, the story will end on a nihilistic note and deprive the player of any record of what they have done. But then, something unexpected happens. Pod 042, named after the answer to life, the universe, and everything, halts the data wipe.

Throughout the game, the Pods, who originally act as helpers to the androids, develop their own sense of consciousness that goes beyond awareness of the main diegesis. Rather, the wizened pods routinely break the fourth wall. In between major story sections, they hold brief conversations on an empty stage not representative of any physical location in the game. They comment on the action thus far and share proposals and predictions on how events will unfurl. The Pods function analogously to a Greek chorus. Their exchanges provide much needed levity in certain situations. At one point, Pod 042 worries about the security of the communication channel, so he contacts Pod 153 over a loading screen, a breach in protocol for which she reprimands him. They can apparently transcend the primary diegesis, and this allows them to interact with the player along the interstitial boundaries between the scripted plot and the player’s emergent narrative.

But in Yoko Taro games, humorous abnormalities like this rarely exist for the purposes of comedy alone. When Pod 042 stops the deletion process, he notes that he’s detecting absorbed memory data for 2B, 9S, and A2 within the collapsing machine network. He claims that he “cannot accept this resolution,” and, after convincing Pod 153 to join him, decides to violate his programming (both as a servant of YoRHa and a scripted video game character) in order to save the protagonists. The Greek chorus comes together with the audience to demand a better ending.

What follows is a “bullet hell” shooting sequence similar to the hacking mini-games the player has encounter several times. However, the enemies this time are the credits themselves. Yoko Taro, the voice actors, the programmers, the animators, the business division, the QA testers, and hundreds of employees from Square Enix and Platinum Games rush in to stop the player from altering fate. Textually, this is conceived as a purge program initiated by the machines to prevent the androids’ data from being recovered. Metatextually, however, it represents a rebellion by the fiction against its artistic demiurges. At last, following 2B’s wishes, the player gets a chance to kill God.

I think the bottom-right panel of the above Grant Snider comic succinctly sums up this final battle.

Crushingly difficult, this sequence will kill the average player over and over and over again. When fighting against the beings that control the universe, you can’t expect it to be easy. With each death, the player is asked a question before they can try again. These include:

“Do you admit defeat?”

“Is it all pointless?”

“Do you think games are silly little things?”

“Do you admit there is no meaning to this world?”

The player must consistently answer “No” to each question in order to try again, even if their cumulative attempts have gotten them nowhere. However, with every death, more messages appear in the background, many encouraging the player to press on. These messages come from players all over the world who’ve completed this section. At this point, the boundary between the internal narrative and the audience’s experience collapses. The characters and player must simultaneously confront failure and press on in the face of despair. A brave, unified story emerges. This could not be replicated in film. Nor in literature, nor music, nor painting, nor sculpture, nor any other medium. NieR: Automata’s ending composes a new lexicon for the language of interactive media.

Following a certain number of failed attempts, the player receives a “rescue offer”. Accepting the offer drastically alters the battle – a ring of ships, representing other players, sacrifice themselves for the host in case they get hit. Meanwhile, all of them fire in unison, decimating the ranks of the developer-gods. As this happens, a new chorus joins the music in the background, signifying the unity in everyone’s dream for a better future. This chorus consists of the voices of much of the development staff, including Yoko Taro himself. Even the gods contribute to this dream.

One final cutscene after the battle reveals that the Pods have rebuilt 2B, 9S, and A2 with all of their original memories intact. Pod 153 warns that the cycle of violence could begin anew, leading them to the same conclusion as before, which Pod 042 accepts as a possibility. However, he places his faith in the potential of a brighter future. After all, 2B no longer has a reason to kill 9S; 9S no longer has a reason to kill A2; A2 no longer has a reason to kill machines; machines no longer have a reason to kill androids. How they find meaning outside of the conflict that’s defined their existence is up to them, which remains an intimidating prospect in its own right.

But 042, the enlightened fool, who looks “very silly” by his own admission, offers words of wisdom:

“A future is not given to you. It is something you must take for yourself.”

The scene gradually fades to black. Pod 042 addresses the player directly and asks one final request. In order to contribute a “rescue offer”, like the one the player received to reach the ending, the player must donate all of their data. The significance of the sacrifices made by other players’ data during the final shooting sequence becomes clear. In order for everyone to have a happy ending, the player must make a sacrifice and pay it forward. Pod 042 reminds the player that whoever they save probably won’t even know them; they might even hate them. The erasure of data here feels different from that of the first NieR. In the original game, the request felt more coercive, which reflected its themes of inevitability and futility. In Automata, it feels altruistic, and it’s even optional. A player can witness the final ending and then refuse to surrender their data. But the game expects its audience to be moved, and rightfully so. Nier: Automata uses its medium to its fullest extent and demands to be taken seriously. You can’t even reach this ending if you admit that “games are silly little things”. In a game obsessed with negative responses to grief, the player receives the opportunity to take their suffering, find meaning in it, and turn it into compassion for others.

With Automata’s ending, many mysteries still remain regarding the overarching plot of the series. But that matters little. Automata leads the Drakengard/NieR story arc on violence to its natural conclusion – healing.

VIII. An Exciting Observation on the Potential of Games as Art

Despite my aforementioned dizzying standards for what qualifies as “art”, I admit that the definition of art remains as mutable as ever. But one thing that I think many people will agree with is that art is moving. Something that inspires an intense emotion or propagates itself by inspiring other artists – there must be some value in that.

Even disgusting art, like the first Drakengard game, elicits a deep emotional response and engages with its audience on a more intimate level than most media. Art might provoke depression by reminding you of the futility of life. Or it might offer new insights into your life’s meaning and point to an avenue for healing. Or maybe it could inspire you to write a 10,000 word literary critique of a video game about leggy androids with katanas.

Nier: Automata is a genre-defining accomplishment. Yoko Taro has achieved something I previously thought was impossible. I suppose Pod 042 was right; there’s always the possibility for a future different from the one we expect.

– Hunter Galbraith

Just a guy who came across this from Yoko Taro’s retweet. I just wanted to say that this is a great essay! I especially enjoyed reading your section on the analysis of ending [E] and its thematic comparisons to previous Taro games. I hope you can continue to write this kind of stuff, although it’s rare that a game will illicit such an essay discussing art and philosophy. Anyway, I don’t have much to say besides giving you props!

LikeLiked by 3 people

Thank you very much! Glad you enjoyed it.

LikeLike

I’m not well versed in either literature or philosophy yet I love reading about the philiosophical tendencies in Automata and Taro’s other games. Mostly due to the fact that I’m barely able to figure out 30% of it by myself. I’m grateful for this incredibly well written and insightful essay.

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you liked it. Don’t worry about not understanding everything. That’s pretty much a major theme in the game. And I didn’t find all of this on my own. So many of the points here just dawned on me while debating the game with friends who’d noticed all sorts of different stuff.

LikeLike

Hello! I’m a NieR fan from China, just want you to know your point in this essay’s so interesting as well as inspiring, that I can’t wait to share it with my Chinese friends. Can I translate this essay and post it to weibo.com? Of course I’ll do my best to explain your intention in Chinese and show the link of this page and your name on my translation. Wait for your reply. 🙂

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you very much for the kind words! As long as you credit me, I don’t have a problem with you translating the essay. I’m amazed that you enjoyed it so much that you’d want to translate something so long! Go ahead! Thank you for your passion and patronage!

LikeLike

Thank you very much! Now that you said it, it may take some time for its length, will inform you once it’s done!

LikeLike

This was a great article. The idea of the censored word meaning “kill” rather than “fuck” was a pretty big mind-blower for me. I’m not even sure it’s easy to interpret it as “kill”, but rather some word outside of the English lexicon that could represent the idea of the intersect between sex and violence.

Thank you for the write-up! You have a real gift for this – I’d love to see more.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for reading! I was hardly the first person to notice the ambiguity of the censored text – there’s been a lot of great discussion about that in various communities. I’ll be sure to publish some more stuff soon!

LikeLike

Well, there’s an interesting debate on the topic here https://www.reddit.com/r/nier/comments/62fkee/regarding_the_during_the_second_playthrough/?st=j1iqgmj1&sh=f8a598f6.

In short, the original Japanese indicates that the missing verb must end with -su in the basic form (Japanese verbs have multiple forms, and the suffix -shitai at the end of the verb is shown, which means the verb must end with -su in its basic form). And there are several words that could work, like “korosu” (kill), “aisuru” (love) and “okasu” (rape/violate, though I think it can be used similarly to fuck). All of these have interesting implications (and there are even more possibilities in the link), but the last I brought up is the most shocking and matches your idea of a word representing an intersection of sex and violence. It’s uncomfortable to admit, but rape is actually kind of the perfect word for that concept, and is absolutely something within the English lexicon.

Crazy stuff. Also interestingly, apparently the Italian translation uses more *** asterisks, and doesn’t fit any word for kill, and fits a word closely analogous with fuck perfectly. Apparently something similar is true for the French localization.

In any case it is really interesting how making just one verb unclear makes for interesting debate over a character’s feelings and motivations. I’m personally of the belief that it is 60% likely to be close to kill, and 40% likely to be closer to fuck, and I agree with those who point out that the censoring may be placed intentionally to reflect 9S’ own mixed feeling and emotions and that he could want to do all of the possible verbs to/with her. Rape is particularly dark, but the Japanese word that fits best with “fuck” is more similar to rape, and rape fits in the four letter space in English, so that’s a pretty valid if truly disturbing possibility. Combined with the sexual imagery of his stabbing of 2B’s doppelgangers in both his memories and the tower, it certainly works as an intersection of sex and violence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Excellent insight! Thank you!

LikeLike

No thank you! This article made me appreciate more of the hidden intricacies of the game, and in particular relieved my dissapointment with how inconsequential Adam and Eve seemed to be (among many other things). I’m glad I could provide some more information to help interpret the game with.

LikeLiked by 1 person

In my opinion, it’s a case of intentional ambiguity. You can give it any of the three readings proposed, although I find the notion of 9S wanting to rape 2B in revenge novel and interesting. There’s a lot of shitty and terrible readings of Nier: Automata, but yours is pretty good. And I’ll get to complimenting the essay’s author later.

LikeLike

Hey thanks for the great article. You pretty much put things together that i’ve been thinking the entire time. The philosophy part especially is very insightful, since i don’t really know much about it. Great job man!

LikeLiked by 1 person

I’m glad you enjoyed it. I really appreciate that you read through all of it – it’s a bit lengthy, to say the least.

LikeLike

It’s a great article so ofcourse i enjoyed it. Btw there’s more interpretation of Adam and Eve topic from reddit that i find interesting to add https://www.reddit.com/r/nier/comments/668vit/spoilers_just_me_rambling_on_about_adam_and_eve/

I guess their story is more on the lore and not the overall game story.

Another note i feel like Eve’s rampage was kinda a call back on Popola after Devola’s death or even Jacob and Gideon from original Nier which is as you said on the cycle of violence.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Amazing essay! I’ve never seen such a profound review of a video game. The analyses are so wonderful that I can’t find any matched article in Chinese forums. After finishing NieR: Automata for twice, I really agree with the idea that elaborate video games have more power to move and inspire audiences than traditional media like TV series or movies. I just discouraged my friends who wanted to experience this game’s narrative by watching videos because this would never give them the feelings I had after playing the game.

LikeLiked by 2 people

Thank you very much for reading! I’m glad you enjoyed it, and I hope your friends check the game out, too.

LikeLike

For that matter, I’ve read a lot on the N:A criticism and I haven’t seen a better essay yet. I’ll probably end up getting around to a tagged criticism thread somewhere.

LikeLike

[Drakengard 3 spoilers]

I know this isn’t the central thesis of this post, but I disagree that Drakengard 3 had nothing to say. In fact, I think it’s the antithesis of Automata in almost every single way. In the context of violence, Drakengard 3 would definitely be about the senselessness of it. I feel it is most obvious with Zero’s main goal — suicide. In any video game the death of the player character is basically a game over. For the player to actually be the one to lead her to suicide — to a game over — makes you wonder what the point of a game filled to the brim with violence in the most ridiculous ways from how the blood spatters on the screen to how several characters are characterized by one trait relating to it is. It’s best highlighted in that level where Zero talks about how she got infected by the flower, but that’s in the background because as she talks, you’re killing countless soldiers in a sepia-toned level. At that moment, I couldn’t help but wonder why. The violence is always there to a most senseless, unnecessary, and obtrusive degree. This, I believe, is what Drakengard 3 says. And I think it’s especially important in the context of Automata because Automata is, in some sense, a work that wants to prove Drakengard 3 wrong. It’s funny how their nearly impossible final bosses contrast each other because Drakengard 3’s just damns the world with no Intoners to keep it in balance, and Automata’s is all about hope and healing.

There are several other aspects worth covering like how it plays with history with how all of its endings add to the worldbuilding yet none of them actually lead to the original Drakengard but I think (and hope! haha) my point’s clear already.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you for the analysis! I’ve had a lot of trouble getting a clear reading on Drakengard 3. It’s really entertaining (for the beginning and end, at least; the middle kind of drags), especially with all the fourth-wall breaks and such. On the first playthrough, it feels like Yoko Taro went from making a abstract, borderline horror game (Drakengard 1) to a somber tragedy (Nier) to a quirky, violent sex-comedy (Drakengard 3). I found that really impressive, and I appreciated the obvious self-parody that was going on throughout it. I still found it difficult to engage with many of the characters though, especially coming off the original Nier, which, admittedly, is a tough act to follow. It’s still worlds better than Drakengard 2, which hardly has any redeeming factors, in my opinion. I find it really funny that most fans completely ignore it at this point.

Anyway, thank you very much for reading and giving your thoughts on Drakengard 3. I considered that I wasn’t quite fair to it, so I appreciate your analysis.

LikeLike

Late to the party but great article! Every little detail I noticed when I was playing the game are all covered in this essay and even more, not to mention well written and informative.

My 2 cents on the topic of ****: I think those asterisks are actually, literally what Adam said (they were talking through text after all). There’s no censor. It still made 9S went completely denial because he knew exactly what Adam was implying and the duality of being both “fuck” and “kill” or even “rape” intensified 9S feeling even further. Also since 9S was in the machine network at that time, his consciousness is exposed to other machines directly and therefore, Adam’s intention can be very easily communicated to 9S through a formless transmission, which can be even more powerful than word if that’s the case since he’s sending his feeling, expression directly into 9S. If this is not the case though, the likeliness is lessen but I still stand by this hypothesis.

Furthermore, it’s a M rated game and the developers didn’t need to nor did they censor such word aside from only that moment (funny enough, in the Japanese dub when 9S voiced his opinion on Jean Paul’s character, his word was censored). Adam censored it himself doesn’t make any sense either, he shouldn’t be aware of the players.

Other than that, if my hypothesis is wrong then I place my bet on rape since it carries both the connotation of violence and sex. 9S doesn’t necessarily have to kill 2B after all, he could just release his frustration by violently raping her and it would work just as well. Too well even.

Actually I kinda want to see that happens, sex with both feeling of love and hate is the best kind of sex (from a voyeuristic view)

LikeLike

Thank you for reading! I’m glad you enjoyed it.

From what I understand, Jean-Paul’s name being censored has to do with him originally being named Sartre, and that was what the VAs recorded. But apparently Square Enix ran into some legal trouble with this, as the estates of both Jean-Paul Sartre and Simone Beauvoir are very protective of usage rights for their namesakes. So they changed the character’s names in text and just decided to bleep out what 9S says out loud rather than re-record it.

LikeLike

Great article. Before Automata, Yoko Taro didn’t really achieved commercial success of his previous games and people (fans) generally see those as hidden gems among the giants like final fantasy. Now that Yoko has gained public attention and I am glad that his attempt of putting out his philosophical thoughts and the topic of meaning of life has been successfully delivered in this game. For me, to put the creator’s true intention (especially philosophical topic ) into a commercial production is very difficult as the normal consumers won’t even want to put their time to invest in it. Normal reviewers like ign, gamespot all give a low score on Yoko’s previous games but I cannot blame them as games for them are supposed to be fun and not studying them like crazy to give a review no one can understand. Still I am glad Yoko finally make a game with publicly attractive combat system while maintaining his own style of story telling and philosophical elements.

LikeLiked by 1 person

Thank you! I am very glad Yoko Taro is finally getting the recognition he’s deserved. And it allows me to be endlessly smug because this is what I’ve been saying all along. 🙂

LikeLike

All right I’m just gonna dump this here because I suspect you don’t check your reddit account regularly; re A2’s name:

One interpretation of ‘et tu’ is that it was a reference to a contemporary stock phrase with the general meaning of ‘they’ll come for you next’. This, obviously, has some applicability to A2’s character.

Also do you have a link to your 6-year-old video that you mention in section I?

LikeLiked by 1 person

Also shit I can’t edit to say this but this essay is really really good and I happened to read it right after trying to articulate the exact same idea of games being a medium ill-suited to art to someone on IRC and it says everything I wanted to and more.

LikeLike

Thank you very much for reading! I think the first section is a bit long-winded and probably needs editing, though. It’s definitely been the most controversial part.

And yeah, I think A2’s name could definitely imply that as well.

As for the old video, it’s still floating around online somewhere, but I would probably be too embarrassed to actually post it and claim ownership. It’s a complete strawman argument for the sake of “comedy” (and I don’t have enough quotation marks for that), so you’re not missing out on any worthwhile content. I was, like, 16 or 17 when I made it, so it doesn’t really live up to my current standards. I might post an archive of old stuff at some point, but for the sake of my dignity, however small it may be, I think I’ll just leave it as it is for now.

LikeLike

this was an absolutely incredible, touching (and thankfully clear) analysis, thank you so much. I went into NieR:Automata with similar conclusions about Drakengard and NieR’s themes like you described, so I knew I was gonna be looking for something, and the game completely blew me away – and this essay filled in some parts I missed and brought it all together. Really wonderful, thank you for sharing!!!

LikeLike

Thank you for reading! I’m glad you enjoyed both the game and the article. It means a lot to me.

LikeLike

I wanted to read the whole essay looking for reasons to buy “NieR: Automata”. I really enjoyed the first part up until the moment you started writing about the game itself and you’ve mentioned there will be spoilers ahead. Since I haven’t played it yet (though I’m planning on it) I couldn’t go all the way to the end. I will get back after I finish the game and tell more.

LikeLike

Haha, I actually think the first part of this essay is easily the weakest, but I’m glad you enjoyed it anyway. I hope you enjoy the game as well. Thank you for reading!

LikeLike

This is an extremely well-written essay and one of the best analyses of Nier:Automata I’ve seen.

One thing that occurred to me while reading your discussion of the protagonist names is that perhaps A2’s name is a reference to the line “Et tu, Brute?” from Shakespeare’s Julius Caesar. After all, the first thing she says when we encounter her is “Command is the one that betrayed you.” I’m kind of surprised I haven’t encountered this idea anywhere else (it might already be out there, but I haven’t seen it), especially since the idea that 2B’s name is referencing Hamlet comes up frequently in discussions of the game.

Like I said, this idea just now popped up in my mind and so I haven’t yet considered how accurate it is or what its further implications might be. I’d be interested to hear what you think!

LikeLike

This point was actually brought up by PhantomHoover above! ^ And I think there’s a lot of credence to that theory. It’s not as if Yoko Taro is unfamiliar with Shakespeare or anything (considering his 100% faithful and accurate rendition of Romeo and Juliet).